Two federal tax credits have encouraged renewable energy in the United States:

States offer added incentives, making renewables even easier to implement from a cost perspective.

A renewable portfolio standard requires electric utilities to deliver a certain amount of electricity from renewable or alternative energy sources by a given date. State standards range from modest to ambitious, and qualifying energy sources vary. Some states also include “carve-outs” (requirements that a certain percentage of the portfolio be generated from a specific energy source, such as solar power) or other incentives to encourage the development of particular resources. Although climate change may not be the prime motivation behind these standards, they can deliver significant greenhouse gas reductions and other benefits, including job creation, energy security, and cleaner air. Most states allow utilities to comply with the renewable portfolio standard through tradeable credits that utilities can sell for additional revenue.

In states with a renewable portfolio standard, utilities consider cost, intermittency and resource availability in choosing technologies that satisfy this requirement.

In the U.S. transportation sector, The Energy Policy Act of 2005 created a Renewable Fuel Standard that required 2.78 percent of gasoline consumed in the United States in 2006 to be renewable fuel.

The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 created a new Renewable Fuel Standard, which increased the required volumes of to 36 billion gallons by 2022, or about 7 percent of expected annual gasoline and diesel consumption above a business-as-usual scenario.

Renewable energy comes from sources that can be regenerated or naturally replenished. The main sources are:

All sources of renewable energy are used to generate electric power. In addition, geothermal steam is used directly for heating and cooking. Biomass and solar sources are also used for space and water heating. Ethanol and biodiesel (and to a lesser extent, gaseous biomethane) are used for transportation.

Renewable energy sources are considered to be zero (wind, solar, and water), low (geothermal) or neutral (biomass) with regard to greenhouse gas emissions during their operation. A neutral source has emissions that are balanced by the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed during the growing process. However, each source’s overall environmental impact depends on its overall lifecycle emissions, including manufacturing of equipment and materials, installation as well as land-use impacts.

Large conventional hydropower projects currently provide the majority of renewable electric power generation worldwide. With about 1,170 gigawatts (GW) of global capacity, hydropower produced an estimated 4,370 terawatt hours (TWh) of the roughly 26,000 TWh total global electricity in 2020.

The United States is the fourth-largest producer of hydropower after China, Brazil, and Canada. In 2011, a much wetter than average year in the U.S. Northwest, the United States generated 7.9 percent of its total electricity from hydropower. The Department of Energy has found that the untapped generation potential at existing U.S. dams designed for purposes other than power production (i.e., water supply, flood control, and inland navigation) represents 12 GW, roughly 15 percent of current hydropower capacity.

Hydropower operational costs are relatively low, and hydropower generates little to no greenhouse gas emissions. The main environmental impact is that a dam to create a reservoir or divert water to a hydropower plant changes the ecosystem and physical characteristic of the river.

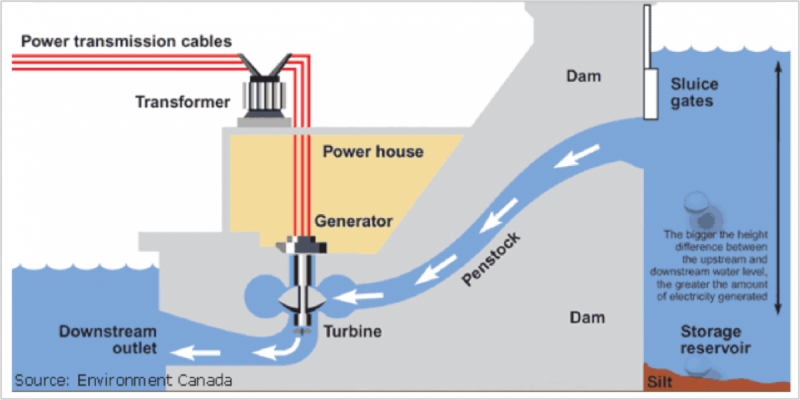

Waterpower captures the energy of flowing water in rivers, streams, and waves to generate electricity. Conventional hydropower plants can be built in rivers with no water storage (known as “run-of-the-river” units) or in conjunction with reservoirs that store water, which can be used on an as-needed basis. As water travels downstream, it is channeled down through a pipe or other intake structure in a dam (penstock). The flowing water turns the blades of a turbine, generating electricity in the powerhouse, located at the base of the dam.

Small hydropower projects, generally less than 10 megawatts (MW), and micro-hydropower (less than 1 MW) are less costly to develop and have a lower environmental impact than large conventional hydropower projects. In 2019, the total amount of small hydro installed worldwide was 78 GW. China had the largest share at 54 percent. China, Italy, Japan, Norway and the United States are the top five small hydro countries by installed capacity. Many countries have renewable energy targets that include the development of small hydro projects.

Hydrokinetic electric power, including wave and tidal power, is a form of unconventional hydropower that captures energy from waves or currents and does not require dam construction. These technologies are in various stages of research, development, and deployment. In 2011, a 254 MW tidal power plant in South Korea began operation, doubling the global capacity to 527 MW. By the end of 2018, global capacity was about 532 MW.

Low-head hydro is a commercially available source of hydrokinetic electric power that has been used in farming areas for more than 100 years. Generally, the capacity of these devices is small, ranging from 1kW to 250kW.

Pumped storage hydropower plants use inexpensive electricity (typically overnight during periods of low demand) to pump water from a lower-lying storage reservoir to a storage reservoir located above the power house for later use during periods of peak electricity demand. Although economically viable, this strategy is not considered renewable since it uses more electricity than it generates.

Environment Canada, 2012

Wind was the second largest renewable energy source worldwide (after hydropower) for power generation. Wind power produced more than 6 percent of global electricity in 2020 with 743 GW of global capacity (707.4 GW is onshore). Capacity is indicative of the maximum amount of electricity that can be generated when the wind is blowing at sufficient levels for a turbine. Because the wind is not always blowing, wind farms do not always produce as much as their capacity. With around 290 MW, China had the largest installed capacity of wind generation in 2020. The United States, with 122.5 GW, had the second-largest capacity; Texas, Oklahoma, Iowa, and Kansas provide more than half of U.S. wind generation, with Texas greatly leading all other states in installed capacity, at 27 percent of the U.S. total. In 2019, wind energy overtook hydropower for the largest share of renewable generation in the U.S., providing 8.4 percent of electricity in 2020.

Although people have harnessed the energy generated by the movement of air for hundreds of years, modern turbines reflect significant technological advances over early windmills and even over turbines from just 10 years ago. Generating electric power using wind turbines creates no greenhouse gases, but since a wind farm includes dozens or more turbines, widely-spaced, it requires thousands of acres of land. For example, Lone Star is a 200 MW wind farm on approximately 36,000 acres in Texas. However, most of the land in between turbines can still be utilized for farming or grazing.

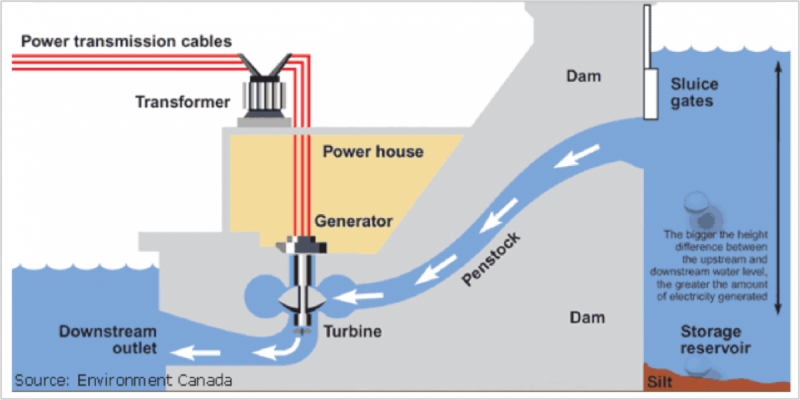

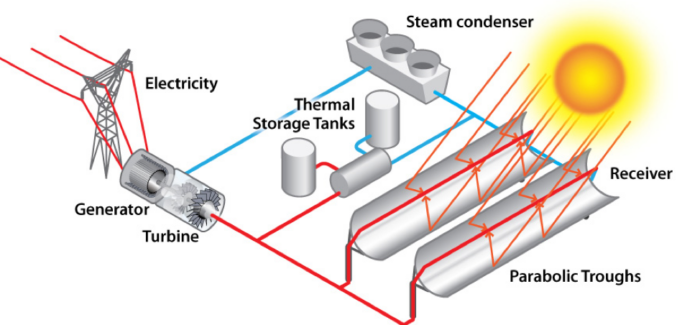

Average turbine size has been steadily increasing over the past 30 years. Today, new onshore turbines are typically in the range of 2 – 5 MW. The largest production models, designed for off-shore use can generate 12 MW; some innovative turbine models under development are expected to generate more than 14 MW in offshore projects in the coming years. Due to higher costs and technology constraints, off-shore capacity, approximately 35.6 GW in 2020, is only a small share (about 5 percent) of total installed wind generation capacity.

Solar energy resources are massive and widespread, and they can be harnessed anywhere that receives sunlight. The amount of solar radiation, also known as insolation, reaching the Earth’s surface every hour is more than all the energy currently consumed by all human activities each year. A number of factors, including geographic location, time of day, and weather conditions, all affect the amount of energy that can be harnessed for electricity production or heating purposes.

Solar photovoltaics are the fastest growing electricity source. In 2020, around 139 GW of global capacity was added, bringing the total to about 760 GW and producing almost 3 percent of the world’s electricity.

Solar energy can be captured for electricity production using:

Solar hot water heaters, typically found on the roofs of homes and apartments, provide residential hot water by using a solar collector, which absorbs solar energy, that in turn heats a conductive fluid, and transfers the heat to a water tank. Modern collectors are designed to be functional even in cold climates and on overcast days.

Electricity generated from solar energy emits no greenhouse gases. The main environmental impacts of solar energy come from the use of some hazardous materials (arsenic and cadmium) in the manufacturing of PV and the large amount of land required, hundreds of acres, for a utility-scale solar project.

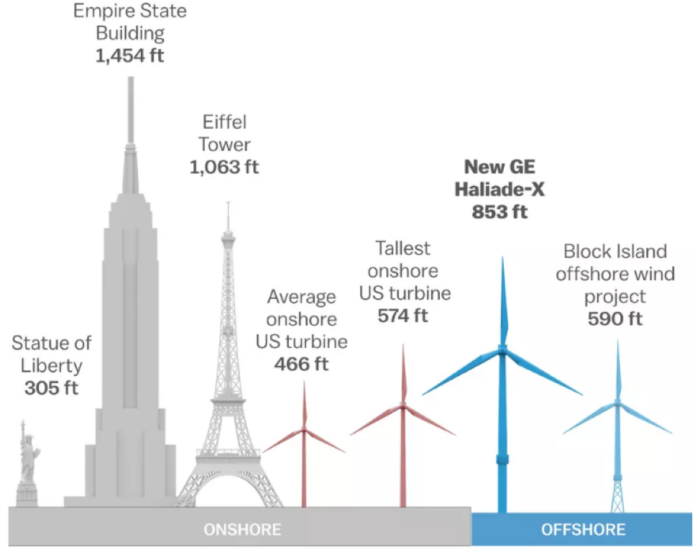

Solar collectors (i.e., parabolic troughs) capture and concentrate sunlight to heat a synthetic oil called therminol, which then heats water to create steam. The steam is piped to an onsite turbine-generator to produce electricity, which is then transmitted over power lines. On cloudy days, the plant has a supplementary natural gas boiler.

Biomass energy sources are used to generate electricity and provide direct heating, and can be converted into biofuels as a direct substitute for fossil fuels used in transportation. Unlike intermittent wind and solar energy, biomass can be used continuously or according to a schedule. Biomass is derived from wood, waste, landfill gas, crops, and alcohol fuels. Traditional biomass, including waste wood, charcoal, and manure, has been a source of energy for domestic cooking and heating throughout human history. In rural areas of the developing world, it remains the dominant fuel source. Globally in 2019, bioenergy accounted for about 11.6 percent of total energy consumption. The growing use of biomass has resulted in increasing international trade in biomass fuels in recent years; wood pellets, biodiesel, and ethanol are the main fuels traded internationally.

In 2020, global biomass electric power capacity stood at 145 GW, increasing 5.8 percent from the previous year. The United States had 16 GW of installed biomass-fueled electric generation capacity. In the United States, most of the electricity from wood biomass is generated at lumber and paper mills using their own wood waste; in addition, wood waste is used to generate the heat for drying wood products and other manufacturing processes. Biomass waste is mostly municipal solid waste, i.e., garbage, which is burned as a fuel to run power plants. On average, a ton of garbage generates 550 to 750 kWh of electricity. Landfill gas contains methane that can be captured, processed and used to fuel power plants, manufacturing facilities, vehicles and homes. In the United States, there is currently more than 2 GW of installed landfill gas-fired generation capacity at more than 600 projects.

In addition to landfill gas, biofuels can be synthesized from dedicated crops, trees and grasses, agricultural waste, and algae feedstock; these include renewable forms of diesel, ethanol, butanol, methane, and other hydrocarbons. Corn ethanol is the most widely used biofuel in the United States. Roughly 39 percent of the U.S. corn crop was diverted to the production of ethanol for gasoline in 2019, up from 20 percent in 2006. Gasoline with up to 10 percent ethanol (E10) can be used in most vehicles without further modification, while special flexible fuel vehicles can use a gasoline-ethanol blend that has up to 85 percent ethanol (E85).

Closed-loop biomass, where power is generated using feedstocks grown specifically for the purpose of energy production, is generally considered to be carbon dioxide neutral because the carbon dioxide emitted during combustion of the fuel was previously captured during the growth of the feedstock. While biomass can avoid the use of fossil fuels, the net effect of biopower and biofuels on greenhouse gas emissions will depend on full lifecycle emissions for the biomass source, how it is used, and indirect land-use effects. Overall, however, biomass energy can have varying impacts on the environment. Wood biomass, for example, contains sulfur and nitrogen, which yield air pollutants sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, though in much lower quantities than coal combustion.

Geothermal provided an estimated 225 TWh globally in 2020, with 97 TWh in the form of electricity (with an estimated 14.1 GW of capacity) and the remaining half in the form of heat. (Total global electricity generation in 2020 was 26,000 TWh).

In the United States, nearly 17 TWh of geothermal electricity was generated in 2020, making up about 3.4 percent of non-hydroelectric renewable electricity generation, but only 0.4 percent of total electricity generation. Seven states generated electricity from geothermal energy: California, Hawaii, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon and Utah. Of these, California accounted for 80 percent of this generation.

Traditional geothermal energy exploits naturally occurring high temperatures, located relatively close to the Earth’s surface in some areas, to generate electric power and for direct uses such as heating and cooking. Geothermal areas are generally located near tectonic plate boundaries, where there are earthquakes and volcanoes. In some places, hot springs and geysers have been used for bathing, cooking and heating for centuries

Generating geothermal electric power typically involves drilling a well, perhaps a mile or two in depth, in search of rock temperatures in the range of 300 to 700°F. Water is pumped down this well, where it is reheated by hot rocks. It travels through natural fissures and rises up a second well as steam, which can be used to spin a turbine and generate electricity or be used for heating or other purposes. Several wells may have to be drilled before a suitable one is in place and the size of the resource cannot be confirmed until after drilling. Additionally, some water is lost to evaporation in this process, so new water is added to maintain the continuous flow of steam. Like biopower and unlike intermittent wind and solar power, geothermal electricity can be used continuously. Very small quantities of carbon dioxide trapped below the Earth’s surface are released during this process.

Enhanced geothermal systems use advanced, often experimental, drilling and fluid injection techniques to augment and expand the availability of geothermal resources.